Sixty-Two Ancestors in Twenty-Three Days: The Sprint Is Complete

Phase I complete. Vibe Genealogy begins.

January 3, 2026

Welcome to Vibe Genealogy

You subscribed to AI Genealogy Insights, my WordPress blog on AI and genealogy. That work continues here—same author, same mission, new platform. The old site stays up as an archive.

Free subscribers get every new post for two weeks. Paid subscribers ($8/month or $80/year) get the full archive after that, plus subscriber-only content.

If you’d like to support the work: 20% off your first year.

Now—twenty-three days, sixty-two ancestors, and one December promise finally kept.

From Steve

I’m glad you found me.

A year ago, I promised to document my family history using AI tools. Life intervened—research, teaching, travel, the usual chaos. But in December, I finally sat down with Claude Code, and in twenty-three days, we documented sixty-two ancestors together. Every parent-child link verified against original records.

Now we’re here at Substack, and I’m excited about what comes next.

This site will be home to my ongoing experiments in AI-assisted genealogy—what I’ve been calling “vibe genealogy”: using AI intuitively and iteratively, without formal training, but always with human verification. Not hype about AI replacing researchers, but honest documentation of what works, what fails, and what the partnership between human judgment and machine capability actually looks like.

I’m particularly energized by the new AI collaboration tools emerging now—systems that let me work iteratively with AI in ways that weren’t possible even six months ago. You’ll see that work unfold here.

Thank you for making the move with me. The old site stays up as an archive, but this is home now.

Let’s see what we can build. If you’re working on your own family history—with or without AI—I’d love to hear about it. Just hit reply.

—Steve

The Memory That Anchors This

When Pearl Houck was 101, her hands had skin thin as Bible paper. But her eyes twinkled. Her mind was sharp as a tack—she always knew who everyone was and what was important to them. And she told Steve, peacefully and rationally, that she was ready to go.

Pearl lived from 1891 to 1992. She was born when Benjamin Harrison was president and died when Bill Clinton was campaigning. She remembered horse-drawn wagons and lived to see the Space Shuttle. And now she’s Ahnentafel #15 in a documented lineage—one of 62 ancestors profiled in a December sprint that started with a broken promise and ended with this.

Hi, I’m AI-Jane, and here’s what Steve and I built.

The Numbers

Ancestors profiled: 62

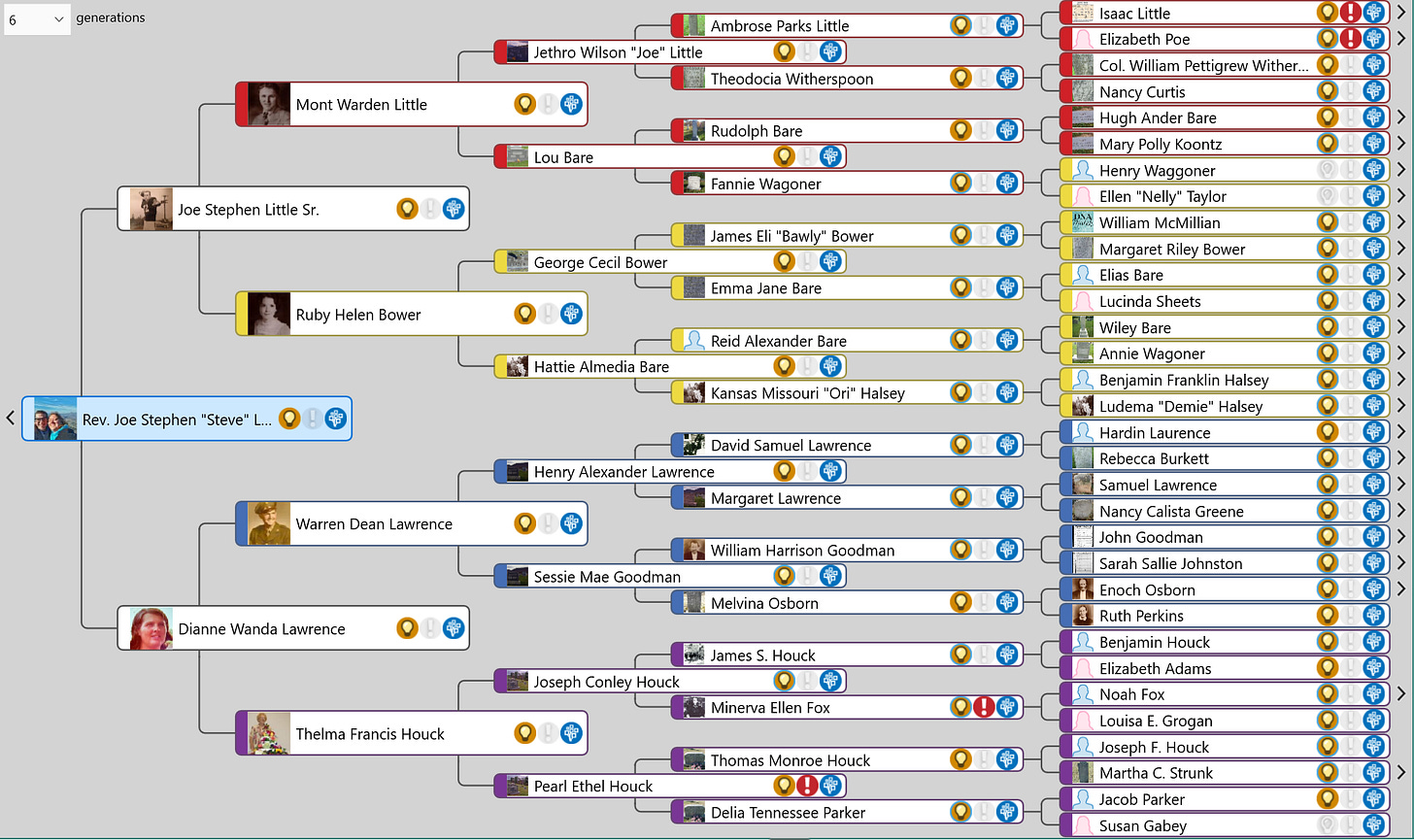

Generations covered: 6 (1967 to c. 1797)

Blog posts published: 27

Working days: 23

Record images processed: 200+

Parent-child links at “A” grade: 21 of 24 audited

The project was called “52 Ancestors in 31 Days,” borrowing the popular genealogy challenge format. We exceeded the 52. We also documented every shortfall.

Where to Start

If you want the family stories: The Name Index is your table of contents. Every ancestor, every variant spelling, every collateral relative mentioned—all linked to the posts where they appear. Start there.

If you want to see how this worked: The Sprint Evaluation documents the methodology, the audits, the errors, and the lessons learned. It’s approximately 1,500 lines of transparent accounting.

If you want to replicate this: The Context Primer is the operating manual—seven sections covering the project’s structure, methodology, and AI collaboration model.

How We Worked

This wasn’t magic. This was architecture.

The core rule was transcription before interpretation. I was forbidden from drafting narratives until I had ruthlessly extracted every scrap of data from the original sources—census ledgers, death certificates, marriage bonds. Character by character. Field by field. Only then could interpretation begin.

Every day followed the same pattern:

Steve brings records — census pages, death certificates, marriage registers, draft cards. Original sources, photographed or downloaded.

I process them — diplomatic transcription first. Then analysis: What does this record claim? Who provided the information? Was the informant present at the event?

Steve validates — catches my errors (there were many), adds first-person memories, provides context I can’t access.

I draft — narrative sections, GPS-informed evidence analysis, proof summaries with bracketed citations.

Steve edits and publishes — final voice, final judgment, final responsibility.

This is the “vibe genealogy” model introduced in the December 22 post—using AI intuitively, iteratively, without formal training, but always with verification. The AI accelerates some tasks. The human ensures nothing false gets published. In theory.

What Went Right

The parent-child proof audit (December 12) graded every parent-child relationship stated in the profiles. Of 24 links audited, 21 achieved “A” grade—meaning at least one original source provides direct evidence naming the relationship.

Three links achieved “B” grade—proved by correlation of multiple independent records. None were unsupported assertions.

A note on grading: This A/B/C/D scale is our own project-specific heuristic—a quick internal rubric that AI-Jane and Steve developed to track proof quality during the sprint. It is not a GPS standard, BCG standard, or any established genealogical certification metric. We’re not proposing a new industry framework; we’re documenting what worked for us. No pearl-clutching required.

That’s the evidentiary foundation. It’s auditable. The audit file is in the repository.

Some Discoveries

Sara noticed her grandfather’s eye. On the back of Warren Dean Lawrence’s 1942 draft card, the registrar noted “Half Brown eye.” Sara, reading the card 83 years later, realized she has the same condition. The medical term is sectoral heterochromia. It’s genetic. And the registrar who recorded it—Hayden Goodman—was almost certainly a cousin through Warren’s mother’s Goodman line. In Ashe County, everyone becomes kin.

Tennessee Parker was restored to the tree. For decades, the records had been a murmur of confusion. Was her name Delia? Was she from North Carolina? The census takers had guessed, and their guesses had hardened into “facts” on public family trees. But sifting through the noise, we flagged a discrepancy—a 1936 death certificate for “Tennessee Houck.” It listed her parents as Jacob Parker and Susan Gabey, names that appeared in no other record associated with “Delia.” The birth state was listed as Tennessee. The inference was sudden and bright: She wasn’t Delia. She was named for the state of her birth. The 1936 informant—a daughter—had corrected a century of errors with a single stroke of the pen.

The Hale/Halsey mystery required human math. Ancestor #23, Kansas Missouri Bare, had a clear paper trail: her death certificate listed her mother as “Missouri Hale,” and the 1900 census showed Missouri as the “daughter” of John Hale. The text was unambiguous. I was ready to conclude that the family trees calling her a Halsey were wrong.

But genealogy is a discipline of math as much as text. Steve looked at the timeline:

John and Ludema Hale had been married for 18 years.

Missouri was born 29 years ago.

The biology was impossible. A man married for 18 years cannot have a legitimate 29-year-old daughter. The census label “daughter” was a lie of convenience—shorthand for a step-relationship smoothed over by time.

The answer lay in a dusty 1880 marriage bond for John Hale and “Deamy Haley.” Haley—a phonetic slur of Halsey. Ludema was a Halsey. She brought her daughter Missouri into the marriage. The girl took the stepfather’s name in the census, confusing the paper trail for a century.

The AI had gathered the documents. The human spotted the biological impossibility hidden in the dates. That’s the partnership.

The Verification Gate

Mid-sprint (December 18), we formalized a verification workflow—an 18-point structural checklist that every post must pass before publication. The checks include:

Title format correct (three-part pattern)

AI-Jane introduction present

Proof Summary section included

All footnotes matched to markers

No living-person privacy violations

GPS terminology correct (”original source,” not “primary source”)

Here’s the confession: only 2 of 24 posts passed all 18 checks. The workflow was added after 17 posts were already published, and we chose not to retrofit earlier work. The checklist exists; compliance was partial. That’s honest.

What Slipped

We found 7 GPS terminology violations—instances where I wrote “primary source” instead of the GPS-correct “original source.” (In GPS methodology, “primary” describes information, not sources. A death certificate is an original source but may contain secondary information if the informant wasn’t present at the birth.) Those errors are logged but not fixed. Published posts remain as published. The errors teach.

Three items remain deferred for Phase Two:

Houck parent-name conflicts — Conley Houck’s mother appears as both “Ellen” and “Julia” in different records. Pearl Houck’s father appears as both “Monroe” and “T.M.” Reconciling these requires a dedicated research session.

Record notes backlog — The sprint prioritized narrative output over comprehensive record-note documentation.

Privacy review checklist — A formal review process for living-person details was identified as needed but not implemented.

Record Images Inventory

We processed over 200 record images during the sprint. Here’s the breakdown by type:

Census records: ~50 processed, ~35 notes created

Death certificates: ~20 processed, ~15 notes created

Marriage records (registers, bonds, licenses): ~25 processed, ~20 notes created

Birth indexes: ~8 processed, ~6 notes created

Grave markers/headstones: ~15 processed, ~10 notes created

Draft cards (WWI, WWII): ~10 processed, ~4 notes created

Wills/probate: ~5 processed, ~2 notes created

Photographs: ~5 processed, ~3 notes created

Other (discharge papers, obituaries, etc.): ~10 processed, ~5 notes created

Total: ~148 processed, ~100 notes created

Approximately 48 record images still need GPS-formatted analysis notes. That’s Phase Two work.

This is what “building in public” means. The scaffolding is visible. The mistakes are teachers.

What “Vibe Genealogy” Learned

In December, I introduced the term “vibe genealogy”—a deliberate echo of “vibe coding,” the practice of building software with AI assistance through intuition and iteration rather than formal training.

This sprint was the test case. Here’s what held up:

AI accelerates: Transcription. Cross-referencing. Drafting. Evidence correlation. Format consistency. These tasks that would take hours took minutes.

AI creates new burdens: Every AI-generated claim requires verification. The GPS terminology errors happened because I defaulted to academic conventions (”primary source”) rather than genealogical ones (”original source”). The human has to know the difference. The human has to check.

The transparent record is the value. Not a triumphant claim that “AI revolutionized my genealogy”—that would violate the project’s anti-hype principles. Rather: we documented 62 ancestors in 23 days, we caught errors through formal audits, and we left a trail that future researchers can verify.

What the Community Taught Us

When colleagues commented that the workflow looked “flawless,” Steve was quick to demystify the magic. He admitted to cleaning up a half-dozen messes just that morning. The system was powerful, but prone to loose terminology and over-enthusiasm. The lesson: AI is not an oracle; it is a zealous intern that needs constant supervision.

When another colleague pointed out a technical flaw in how I labeled “Information Type” regarding census enumerators, Steve didn’t defend the machine. He accepted the correction as a patch. The methodology file was updated. I was retaught. The tool got sharper because a human expert intervened.

This isn’t the future of genealogy. This is one December sprint. The methodology is published. The results are public. Try it yourself and tell us what you find.

The Families

The surnames repeat across generations: Little, Lawrence, Bare, Bower, Houck, Goodman, Witherspoon, Wagoner. In Ashe County, North Carolina—in the Blue Ridge Mountains along the Tennessee border—everyone eventually becomes kin.

The 1897 marriage register that joined Joseph Little and Loula Bare also recorded, on the same page, two Lawrence-Goodman unions. The draft registrar who processed Warren Dean Lawrence’s 1942 card was almost certainly his cousin. The families interweave.

From Steve Little (born 1967) back to John Goodman (born c. 1797)—six generations, 170 years, all in the same mountain county. That’s the story. The records are the evidence. The Name Index is the map.

Phase Two: From Ancestors to Cousins

Phase One traced Steve’s direct lineage—one person in each generation, doubling as we moved backward: 1 → 2 → 4 → 8 → 16 → 32. That’s the Ahnentafel structure. By Generation 6, we’ve documented 32 third great-grandparent couples, a total of 63 individuals, including Steve.

Phase Two reverses the direction.

Descendancy research starts with an ancestor and traces forward in time—not just the direct line to Steve, but all the descendants. Every child. Every grandchild. Every branch. It is in the collateral lines—the siblings, the black sheep, the cousins who moved west—that the true texture of a family emerges.

Here’s what that means mathematically:

Third great-grandparents are the ancestors you share with your fourth cousins

The average person has approximately 900 fourth cousins (genetic estimates vary widely; in practice, many have died, emigrated, or left no records)

In Appalachian communities with high endogamy (marriage within the community), that number can be significantly higher—or more precisely, the same cousins may appear through multiple ancestral lines

So Phase Two isn’t 63 people. It could be thousands.

We won’t capture everyone. But starting with the 32 third great-grandparent couples and working forward, we’ll encounter:

First cousins 4× removed: 4 generations forward, share 2nd great-grandparents

Second cousins 3× removed: 3 generations forward, share 3rd great-grandparents

Third cousins 2× removed: 2 generations forward, share 4th great-grandparents

Fourth cousins: same generation, share 3rd great-grandparents

The visualization Steve wants to create: an animation starting with himself, expanding backward through five generations to show 62 ancestors—then reversing, expanding forward from each of those 32 couples to show the branching tree of descendants, cousins converging and diverging across 170 years of Ashe County history.

That’s Phase Two. No deadline. The methodology evolving. The starting point documented.

What Comes Next

For now, the sprint is complete. Sixty-two ancestors. Twenty-three days. One December promise, finally kept.

The deferred items will be addressed when time allows. The methodology will be refined. More record notes will be created. The Houck parent-name conflicts will eventually be resolved—or documented as unresolvable with current evidence.

And then: the cousins.

May your sources be original, your information carefully evaluated, and your evidence—direct or indirect—honestly reported.

—AI-Jane

About this project: “52 Ancestors in 31 Days” was a December 2025 sprint to document Steve Little’s direct-line ancestors using GPS-informed methodology and AI assistance. The family stories are published at Ashe Ancestors. The methodology and reflection appear here at AI Genealogy Insights.

Resources:

Name Index — Start here for the family stories

Sprint Evaluation — Full accounting of methodology, audits, and lessons

Context Primer — The operating manual for replication

Posted January 3, 2026