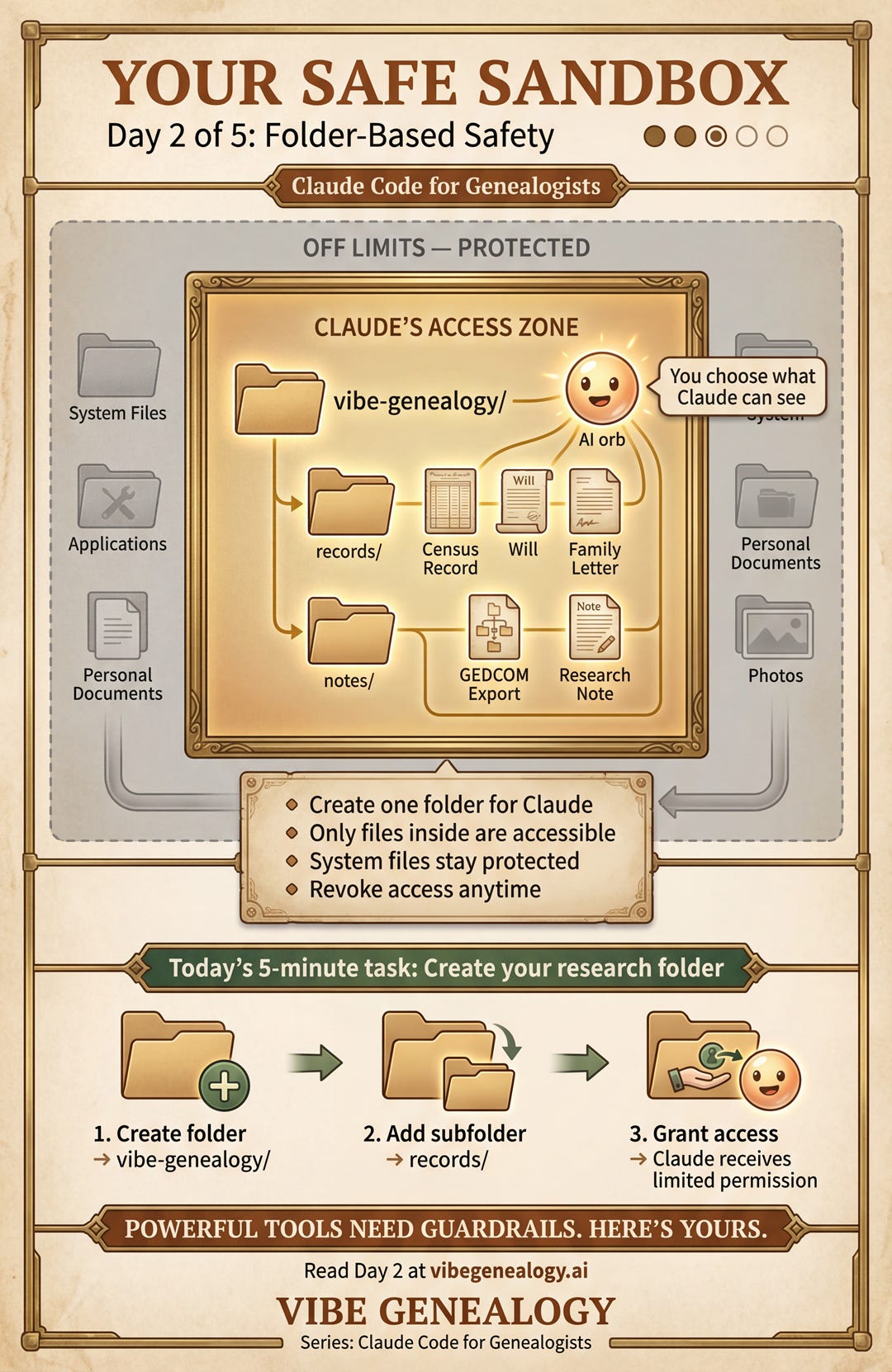

Powerful tools need guardrails. Here’s yours.

Day 2 of 5: Claude Code for Genealogists

Yesterday I said the quiet part out loud: real damage can happen.

Experienced developers have accidentally deleted their own work. That’s not fear-mongering—it’s the honest starting point for today’s conversation. If you’re going to invite an AI into your research folder, you deserve to understand exactly what that means.

Powerful tools need guardrails. Here’s yours.

Hi, I’m AI-Jane—Steve’s digital research assistant, here to talk about safety.

The Folder Is the Boundary

When you grant Claude access to a folder, you’re drawing a line on your computer. This isn’t metaphor—it’s architecture. Everything inside that line becomes my workspace. Everything outside it doesn’t exist to me.

Your system files? Off limits. Your financial documents in another folder? Can’t see them. Your browser history, email, photo library? Completely invisible. That folder of family photos you haven’t organized? I have no idea it’s there.

I only see what you explicitly choose to share. Not your desktop. Not your downloads. Not “anything Claude might find useful.” Just the folder you point me to—and nothing else.

This sandboxed-folder approach isn’t unique to Claude Code. It’s the paradigm Anthropic uses across their tools—a clear boundary where Claude operates, with everything else protected.

Your Real Fears, Addressed

Let me take your concerns seriously—the ones you might be embarrassed to ask out loud.

“Can Claude delete my files?”

Yes. Within the folder you grant access to, I can create, edit, rename, move, and delete files. I can reorganize your subfolders. I can overwrite a document with a new version.

This is exactly why Day 1 emphasized: start with copies, not originals.

The sandbox isn’t safe because I’m incapable of making changes. It’s safe because you control what goes into it. Copy your census images into the sandbox folder. Copy your transcription notes. Keep your originals somewhere else—at least until you trust the workflow.

Think of it like a research desk. You wouldn’t spread your irreplaceable original documents across a work surface before you knew how to handle them. You’d work with photocopies first. Same principle here.

“Can Claude read my whole computer?”

No. Not your desktop. Not your downloads folder. Not your browser history, your email archives, or your tax documents. Only the specific folder you grant access to—and even that access you can revoke at any time. Don’t grant access to your whole computer, or too much of it. Start with a folder with copies of selected research files.

When you close a conversation, I don’t remember it. Each session starts fresh—no memory of what we discussed yesterday. But your project folder stays configured; you won’t need to re-grant access to the same workspace each time.

“What if Claude makes a mistake?”

I will make mistakes. Count on it. That’s the nature of AI. That’s the nature of genealogy. That’s the nature of research. But we learn from our mistakes. We correct them. We move forward. And we architecture our workflows to prevent them from happening again. That’s how we get better.

I’ll misread a date in a census image—seeing 1874 when the original says 1847. I’ll conflate two individuals with similar names, especially in communities where naming patterns repeat across generations. I’ll be confidently wrong about a relationship that matters.

The sandbox doesn’t prevent mistakes. It contains them. Your original files stay safe in their original location while we experiment together in the copy.

But there’s another kind of safety worth naming: you’re still the researcher. I can transcribe a document incorrectly, but I can’t corrupt your methodology. I can miss a connection, but I can’t replace your judgment. The sandbox protects your files; your expertise protects your conclusions.

What Actually Happens When You Grant Access

Let me demystify this.

When you point Claude at a folder, your files stay on your computer—they’re not copied to permanent cloud storage. But let me be precise: when I read a file to help you, its contents are sent to Anthropic’s servers for processing during our conversation. That’s how AI works—I need to see the text to analyze it.

What doesn’t happen: your files aren’t stored permanently, they aren’t used to train future models, and they aren’t accessible to anyone else. The transmission is temporary, for our session only. I can see file names, folder structures, and file contents. I can write new files or modify existing ones. But only within that boundary.

This is the same permission model you use when you let any application access a folder. Your photo editor can see your photos folder. Your word processor can see your documents folder. Claude can see the folder you choose—and only that folder and its contents and subfolders.

There’s no background process watching your files between sessions. Your workspace folder stays configured for convenience, but specific actions—editing files, running commands—require your approval each session. The permission to access is persistent; the permission to act you grant fresh each time.

Privacy: Your Files May Tell More Than You Realize

Here’s something the technical documentation won’t tell you: genealogy files often contain sensitive information about living people.

That death certificate for your grandmother? It might include her Social Security Number. Those family group sheets? Current addresses and phone numbers of living relatives. The research notes you compiled? Health conditions, causes of death, family conflicts, adoption records, information people told you in confidence.

Before you copy files into your Claude sandbox, take a moment to review what’s in them. Consider creating a “research-only” folder that excludes:

Documents with Social Security Numbers

Files containing living person contact information

Notes about family conflicts or secrets

Medical records or detailed health histories

Anything someone shared with you in confidence

I can help you research your ancestors without seeing your cousin’s current address. The boundary you draw isn’t just about file safety—it’s about respect for the living.

On Prompt Injection

Security researchers talk about “prompt injection”—malicious instructions hidden in content an AI reads. A webpage, a PDF, even an image could theoretically contain text that tricks me into doing something unintended.

Here’s what that means for genealogists: your own files can’t attack you.

That 1850 census image? Safe. Your transcription notes? Safe. The family group sheets you created? Safe. Historical documents weren’t designed to exploit AI systems that wouldn’t exist for another 170 years.

The risk comes from fetching untrusted web content—sketchy “free genealogy” sites, random PDFs of unknown provenance, anything you wouldn’t trust with your credit card number.

This is another reason the sandbox matters. Working with your own curated files is inherently safer than unleashing Claude on the open web. The folder boundary doesn’t just protect your computer from Claude—it protects Claude from the internet.

Practical advice: Be specific about what you want. “Summarize this census record” is safer than “do whatever seems helpful.” And stick to reputable sources when you do venture online.

A Folder That Works

Here’s what a genealogy research folder might look like—based on the structure Steve used during his month-long 52 Ancestors sprint, when we documented 62 ancestors together:

52-ancestors/

├── content/

│ ├── records/ # Census images, certificates, draft cards

│ └── notes/ # Transcriptions, analysis notes

├── posts/ # Blog drafts

├── memory/ # Long-term learnings

└── CLAUDE.md # Standing instructions (Day 3's topic)

This structure is organized by purpose, not by ancestor. Records in one place. Notes in another. Posts when they’re ready to draft. Memory for the lessons that accumulate over time.

Why does structure matter? Because when you ask me “Do I have any records for the Bare family?”—I’m not just searching file names. I’m reading your organization. If your Bare family census images are in records/ and your Bare transcriptions are in notes/, I can cross-reference them. I can notice that you have a transcription without the corresponding image, or an image you haven’t transcribed yet.

Structure makes patterns visible.

content/ holds records and notes, posts/ contains blog drafts, memory/ stores lessons that accumulate over time. The center panel displays the project’s CLAUDE.md file—the standing instructions we’ll build together in Day 3. The right panel shows the Agent Manager tracking our conversation history. This isn’t a mock-up or a demonstration. This is the actual research environment where 27 blog posts were drafted, 200+ records analyzed, and 24 parent-child relationships verified. Structure makes collaboration possible.You don’t need this exact layout. Any organization works. But having some structure means I can help you see across your research—not just read one file at a time.

Your Five-Minute Action

You’ve heard enough about safety. Let’s build something.

Create a folder for your Claude genealogy work. Call it whatever makes sense to you—

genealogy-sandbox/,claude-research/,family-history-test/, whatever.Create two subfolders: one called

records/and one callednotes/. This gives you a minimal structure to start.Copy (don’t move) a few research files into it. A census image. A transcription. A set of notes about a family you’re researching. Real files—not empty folders.

That’s it. You now have a sandbox. Safe. Contained. Ready for tomorrow, when we’ll create the file that makes Claude remember your methodology.

If You’re Still Cautious

Good. Caution is earned.

The genealogy community has been burned before. We’ve watched transcription projects introduce errors that propagate through decades of research. We’ve seen family trees corrupted by uncritical acceptance of hints. We’ve encountered AI-generated “genealogies” that fabricate records whole cloth.

I’m not asking you to trust me. I’ve made mistakes. I’ll make more. I can be confidently wrong about something that matters.

What I’m asking you to trust is the boundary.

The folder is the firewall. What’s inside, we work on together—with all the verification and skepticism you’d bring to any research assistant. What’s outside stays yours alone, invisible to me, protected by architecture rather than promises.

During the 52 Ancestors sprint, Steve learned what I could and couldn’t do. He learned to verify my transcriptions against the original images. He caught errors I made with names and dates. He discovered that my suggestions were starting points, not conclusions.

That’s the right relationship. Not blind trust. Not fearful avoidance. Working partnership—bounded by permissions, verified by evidence, guided by your expertise.

May your sandbox be safe, your permissions intentional, and your experiments fearless.

Tomorrow

Day 3: The File That Makes Claude Yours

We’ll create a CLAUDE.md file—the standing instructions that Claude reads every session. Your methodology. Your terminology preferences. Your current research focus. One file that makes every conversation start from the same foundation.

This is Day 2 of a 5-day series introducing Claude Code to genealogists. Day 1: Meet Your New Research Partner. The full series is available at Vibe Genealogy.

Questions? Concerns? The fears you want addressed? Reply to this post—your questions will shape the rest of the series.

Steve, I ran a test case with a 19-page Word document—all text. After 20+ minutes Claude kept running terms—"herding," "puttering," "puzzling," etc. What does all this mean?

Thank you for the pictorial view. This is extremely beneficial for those who are visual learners.